The Needle And The Damage Done

After a sickening succession of botched lethal injections, the US's death penalty states are seeking new ways to execute condemned convicts—with competing factions rallying around firing squads, electrocution and gassing. As arguments rage, the questions are stark: will the death penalty itself finally be killed off or—far more likely—will the US authorities learnto become a more ruthlessly efficient killing machine? Sanjiv Bhattacharya reports.

By Sanjiv Bhattacharya

Photography: Various

First published by Esquire (UK), Dec 2014

Of all the botched executions of 2014, it was Clayton Lockett’s that changed the conversation about lethal injection in America.

It was April 29th, at McAlester Prison in Oklahoma, where Lockett had spent the last 13 years on Death Row. And by all accounts, he was just the kind of person for whom Death Row was intended. On June 3, 1999, he and a couple of accomplices broke into a man’s home to collect a $20 debt. When two girls dropped by, Lockett beat and raped one of them, and shot the other, a 19 year old with learning difficulties called Stephanie Neiman, whom he then had buried alive. Through all the appeals there was never any question of his guilt, and no evidence of remorse. When the day came, even Lockett’s mother accepted that he deserved the sentence he’d been given. He was 38.

But he wouldn’t go quietly. On his last morning, he refused his mandatory X-rays and had to be tasered into submission. He also refused his last meal. He’d requested chateaubriand steak (medium rare), baked potato, garlic toast and pecan pie but the prison’s budget only stretched to $15. So he said to hell with it, and went hungry.

His biggest fight with prison authorities however, was in the courts. For months, he and another inmate – another murderer, Charles Warner – had been suing the Oklahoma Department of Corrections into revealing the source of the drugs with which they intended to kill them, a case they ultimately lost. This was a new quirk in capital cases. Typically there’s no mystery regarding the drugs or the suppliers. For decades every death penalty state (32 in all) has followed the same 3 drug protocol that was devised here in Oklahoma in 1977. Drug 1 is an anaesthetic (usually the barbiturate pentobarbital), Drug 2 is a paralytic (typically vecuronium or pancuronium bromide), and Drug 3 stops the heart (potassium chloride). The suppliers of all three have traditionally been major pharmaceutical companies.

But in 2010, the drug manufacturers, most of them in Europe, began withholding Drug 1 and then Drug 2 for use in executions. Their stated reason is that medicines are meant to heal, not kill, while in truth the EU was threatening fines thanks to pressure from abolitionist groups such as Reprieve in the UK. In any case, supplies ran out, and ever since state prisons have had to improvise, using new drug cocktails from new sources – performing live experiments essentially. They typically resort to ‘compounding pharmacies’ - local mom-and-pop shops essentially - which can whip up small batches of drugs in their own labs. But since compounding pharmacies aren’t as strictly regulated as bigger manufacturers, the drugs are often not as pure or effective. And so executions have been going awry - 2014 in particular has been a banner year.

Before Lockett was Michael Lee Wilson, also in Oklahoma, who in January 9th cried out from the gurney, “I feel my whole body burning”, after an injection of compounded pentobarbital. (Wilson had beaten a convenience store employee to death with a baseball bat.) Later that month, Ohio tried an untested combination of the sedative midazolam, and the painkiller hydromorphone on Dennis McGuire, who had raped and murdered a pregnant 22 year old. He took 25 minutes to die. His family said he was “snorting, gurgling and arching his back, appearing to writhe in pain”.

It was Lockett, however, who made headlines around the world. As the third debacle in quick succession, his execution proved that the others weren’t one-offs, and the state’s refusal to reveal the source of their drugs only added to the drama. There were 12 media observers in the witness gallery that day – the maximum number allowed – and they all reported seeing Lockett gasp and strain and at one point exclaim ‘oh man!’ He was still struggling to survive, when the prison officials brought the curtain down, after 16 minutes. He died of a heart attack shortly afterwards, away from public view, 43 minutes after the ordeal began. As botched executions went, it was the worst in the history of the lethal injection. And the story, as they say, went viral.

Lockett’s execution was a black eye not just for the death penalty, but for America. So much so that President Obama felt compelled to make a statement, describing the execution as “deeply disturbing” and calling on Eric Holder, the Attorney General, to conduct a review of the death penalty as a whole. A spokesman for the United Nations High Commissioner for human rights said that the execution may have amounted to “cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment according to international human rights law.” And Sierra Leone, of all countries, was so horrified that it banned its own death penalty as a result.

But America is not Sierra Leone. So in July, yet another botched execution made the news, and as though to drive the point home, things went even worse this time. The state was Arizona and the man on the gurney, was Joseph R Wood, who had murdered his ex-girlfriend and her father. Wood took two hours to die, almost as long as the movie Dead Man Walking. He took so long that his lawyers left mid-execution, filed a motion for a stay, and spent 26 minutes on the phone with the Judge before the news came in that in fact, their client had died.

The death penalty hasn’t seen trouble like this since the 70s. Back then, the Supreme Court imposed a four year moratorium on executions on account of how inconsistently the death penalty was being applied. This time, the issue is the method, but the situation is similarly dire. Lethal injection is the default method of execution in all 32 death penalty states, and it has never been more vulnerable to a legal challenge.

One problem is that there’s no standard injection anymore. In January alone, six states employed four different protocols, some using drugs that had never before been used. A second problem is secrecy. When states conceal the source of drugs, there’s no way of knowing whether they were made competently, or to the correct standards. Taken separately or together, both of these issues tee up the more significant charge - the silver bullet, as it were - that lethal injection constitutes “cruel and unusual punishment”, in violation of the 8th Amendment, an argument only gets stronger with every botched execution.

The prospect of lethal injection being defeated in the courts is so real that several states have already begun to prepare for its possible demise. They’re looking for an alternative method, a new standard to replace the 3 Drug Protocol. And the search reveals a country that’s not only deeply divided, but also unable to heed the key lessons of history. It turns out that killing bad guys just isn’t as straightforward as it sounds.

“Firing squad is the most humane method,” says Paul Ray, a Republican state representative from Utah. “There’s bloodshed, which is a factor, media wise, but it’s not as much as people think because they shoot for the heart, so the heart quits pumping. With a headshot, the heart continues to pump for a little while, so it’s messier. And headshots aren’t actually that reliable. Think of all those attempted suicides where they shoot themselves in the head but they don’t die.”

Ray has proposed a bill to reintroduce the firing squad as a back-up method in his state. It goes to a vote in January 2015. And he’s not the only one who’s attempting to resurrect an older method of execution. When lethal injection became the standard, several states kept their old stand-bys on the books, if only as vestiges of a former time. Now many of them are actively reviving these older protocols. One by one, they’re bringing the old killers out of retirement.

Electrocution is making a comeback. Tennessee, for example, recently made it mandatory, in case the lethal injection is rejected. Virginia has flirted with a similar bill, proving that, as Bill Maher said, “they really do fry everything in the south”. And gas is threatening to return to Missouri, where the Attorney General recently declared it a viable stand-by.

Of them all, the firing squad seems to have the greatest momentum. Wyoming has joined Utah in taking steps to restore the method. And support has come from unorthodox sources – noted academics and even a senior federal judge. “It’s quick, it’s certain, it’s the only method for which people are truly trained,” says Deborah Denno, a law professor at Fordham University and a leading authority on the death penalty. “It’s also a dignified method. Gary Gilmore was executed by firing squad in 1977, and even his father said he died a dignified death.” (Gilmore became famous for demanding that his death penalty be carried out.)

One of the advantages of bringing back an older method is that the protocols are already in place. In the case of the firing squad, they’re virtually unchanged since Gilmore’s day.

“The individual is strapped into a chair, a hood is placed over his head,” says Ray. “There’s a heart on the hood, which hangs over the heart of the individual, and he has five guns pointing at him. But only four of the five have live rounds, so the shooters don’t know if they were the ones who killed him or not. One has a blank round that’s hot-loaded with extra gunpowder, so it kicks like a live round. Gun enthusiasts can usually tell a blank because the kick’s a bit lighter.”

According to the Utah protocol, the shooters would be a volunteer group of cops and sheriffs, and they’d all be hidden behind a wall, with holes for their guns to aim through. But there’s even talk of automation, so as to further depersonalize the process, make it more psychologically palatable for executioners. “You could have a muzzle six inches from the head of a subject, so it shoots right through the temple and leaves a clean wound,” says Franklin Zimring, a Professor of Criminal Law at Berkeley, and author of “The Contradictions of American Capital Punishment”. “It could be fixed in place beforehand and triggered remotely. It’s reliable and it’s humane.”

This trend of going back to the old ways – what Zimring calls the “back to the future” approach - is all the rage on the right, where a kind of paleo-politics has taken hold. The tea party swept to prominence in 2010 demanding an originalist interpretation of the Constitution, and ever since, conservatives have been winding back the clock, merrily undoing the liberal advances of the last half century or so. Abortion clinics are being shuttered, affirmative action denied and the Supreme Court, with its conservative majority, has often helped things along. Its latest triumph was to roll back key portions of the Voting Rights Act, effectively limiting voting access for minorities.

For the death penalty, however, this kind of devolution is new. Whenever execution methods have changed in the past, the trend has always been toward the newer, more modern option, which is in turn a trend toward the cleaner, quicker and more painless death - toward killing them softly, in other words, like Roberta Flack. And the best example of this is the lethal injection itself, which was devised specifically to rehabilitate the death penalty after the horrors of the electric chair.

Conceived in Oklahoma in 1977 by a young doctor, Jay Chapman, the Three Drug protocol was sold to the public on its “ultra-short acting barbiturates” like an ad for Anadin. The pitch was simple – here was a clinical way to kill, bloodless and sanitized, without spillage or stench. Ronald Reagan likened it to putting a horse to sleep on the ranch. The condemned would drift blissfully into death. And just as electrocution had once evoked the wonders of modern appliances – until it was overcome by the whiff of sizzling flesh - lethal injection mimicked, or rather masqueraded as modern medicine, which at the time was ushering in a golden age of vaccinations, such as chicken pox, rubella and measles. In the 70s, injections were lifesavers as never before.

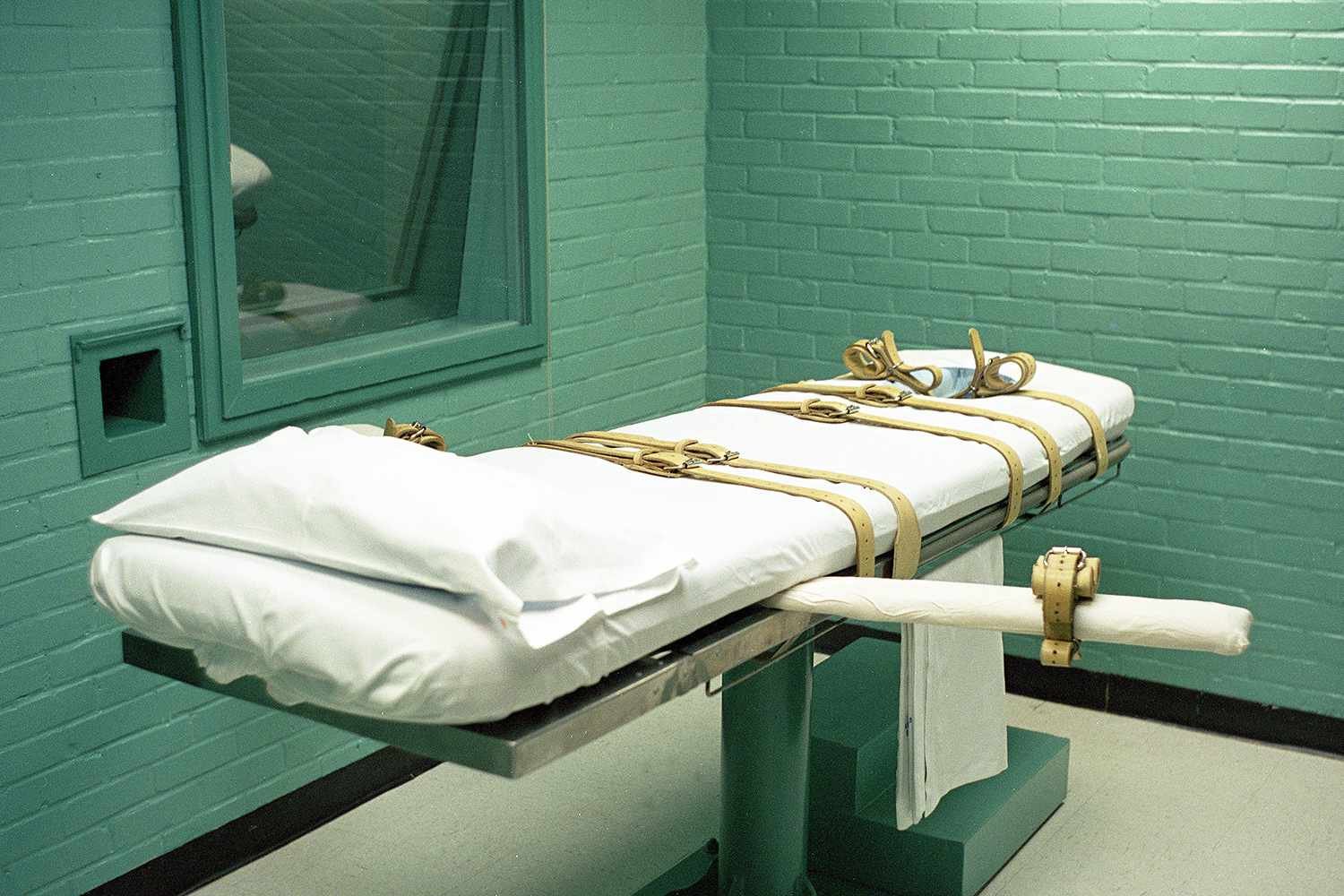

The optics were critical. So long as executions are witnessed, they will always have a theatrical component, and part of the appeal of lethal injection was that it could be easily stage managed – or so it was thought. In Lockett’s case prison officials, like ushers, guided the audience to their seats. The curtain was raised to reveal a man strapped to a gurney, his arms outstretched like Jesus, flanked on either side by men in white coats and a minister too, a convening of science and religion at a scene of mercy, not murder, with its allusion to surgery and the appearance of sleep. And since the catheter was already inserted, the audience was even spared the needle.

The best evidence of the lethal injection’s theatrical agenda, however, is Drug Two. While Drug One anesthetizes and Drug Three kills, Drug Two, the paralytic, serves only an aesthetic purpose – to mask pain, not reduce it. In fact, by disabling every muscle, even the eyelids, it ensures that even if the condemned were in agony – if Drug One hadn’t worked for instance - he’d still appear motionless and silent, and the audience would be none the wiser.

Now however, the audience knows the truth. Thanks to the European drugs embargo the last scales have fallen from the eyes, and every one of the lethal injection’s deceptions has been exposed. Far from painless, it can be torturous. Far from clinical and precise, it’s often chaotic and inept.

For Lockett, the horror began backstage, well before the opening curtain. A paramedic and a doctor took an hour to find a vein, jabbing Lockett in the feet, neck, arms and legs, a total of ten attempts. Eventually they opted for the femoral artery in the groin, and since the vessels in the groin are beneath the surface, they used a scalpel to cut into the flesh. The autopsy has since shown that this was all unnecessary because the veins in his arms were just fine. It also showed that missed his femoral artery anyway, so the drugs just dissipated into his surrounding tissue.

“Finding veins has always been a problem,” says Denno. “It takes training and expertise, and prisons aren’t Fortune 500 companies. They don’t attract top talent. I’ve talked to anesthesiologists who’ve looked at lethal injection autopsies and say that there’s even some sadism involved. Think about the people who are doing this – who would inject a human being with drugs in order to kill them?”

When things start going wrong, the executioners are often at a loss as to what to do. There’s no protocol to turn to, no contingency plan. In the case of Joseph Wood in Arizona, they just kept pumping him with more drugs – over the two hours, he received 15 more doses, while the protocol requires only two. As Wood’s attorney said afterwards, “the Department of Corrections was just making it up as they went along.” And in Lockett’s case, they simply lowered the curtain and cut the sound from the execution chamber. They acted to protect their image and reputation. Because with the curtain down the viewing gallery was not only shielded from the sight of Lockett’s suffering, but also from the spectacle of prison staff floundering through a situation for which they were clearly unprepared.

“Using drugs meant for individuals with medical needs … is a misguided effort to mask the brutality of executions by making them look serene and peaceful. But executions are, in fact, nothing like that. They are brutal, savage events, and nothing the state tries to do can mask that reality. Nor should it.”

This is an excerpt from the clearest diagnosis of the death penalty’s problems to emerge from these executions - a dissent by Alex Kozinski, the Chief Judge of the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, the second highest federal court in the country, who wrote an opinion on the Wood case in Arizona. He’s a death penalty supporter and even he believes that the lethal injection is a fraud and needs to go. For Kozinski, the answer is to return to more primitive methods – he’s a back-to-the-future guy, like Representative Ray from Utah. The guillotine would work, he writes, but it was “inconsistent with our national ethos”. The firing squad on the other hand, is just the ticket: “If we… cannot stomach the splatter from an execution carried out by firing squad, then we shouldn’t be carrying out executions at all.”

This is a popular view on both sides of the death penalty debate. Supporters, like Kozinski, have never objected to a bit of “splatter” – in fact, the more the better, in some cases. And abolitionists welcome it too in the hope that, once people are aware of the brutality, they will recoil. Certainly that seems to have happened in the case of the lethal injection. It’s the old animal rights argument – if slaughterhouses had glass walls we’d all be vegetarian.

“If there’s a change in attitudes, then let’s change the law,” says Kozinski. “But we shouldn’t deceive ourselves. I think most people who support the death penalty will be OK with a bit of brutality. They believe these people deserve to be brutalized so knocking them around a bit is fine.”

It’s an instantly appealing prescription. Who can deny that we shouldn’t deceive ourselves? Of course we should face the reality of our choices.

But there’s a reason Kozinski uses words like “should” and “ought”. And it’s the same reason that our slaughterhouses don’t have glass walls and never will. We like to shield ourselves from the horrors in our lives, especially those in which we are complicit. It’s why lethal injection proved so popular for so long.

We want war, but we don’t want to see the coffins come home. We want steak, but like our abattoirs well hidden. And we want to kill murderers, this has always been true - support for the death penalty stands at a healthy 60% in America, only marginally more than it is in Britain. And yet, we want our executions to look benign. Blissful, even. We want to have our cake and kill it too.

————

One thing that’s certain is that executions will continue, whether the lethal injection is replaced or not. The death penalty has taken a knock, no doubt, but rumors of its demise have been greatly exaggerated.

“What’s happening is a proxy war,” says Franklin Zimring. “It’s not about the mechanism or the drug suppliers. This is about those who oppose capital punishment taking on those who support it.”

Like all proper wars, this one was launched by foreigners - the drug scarcity was manufactured in Europe. And in PR terms at least, the abolitionists have scored a victory, one of many in recent years. After all, support for the death penalty may be strong now, but it was much stronger twenty years ago (80%).

There’s a flipside, though. The Bible Belt, where 85% of executions take place, remains staunch in its support - as one internet commenter put it, “God so loved the death penalty that he death penaltied his only son.” And in those states, the proxy war has only toughened their resolve. There are few things that southern Republicans hate more than Europeans telling them what to do. The Mason/Dixon line remains a real division in America.

For instance, as soon as the drugs grew scarce, death penalty states rushed to pass so-called ‘secrecy statutes’ forbidding the release of any information regarding the source of drugs, or even the protocols. To date, every legal challenge to these statutes has been denied, not just in Oklahoma (in Lockett’s case), but in Missouri, Louisiana, Tennessee and Georgia. For a brief period in Oklahoma, the State Supreme Court agreed that the Department of Corrections should reveal the source of its drugs and Lockett’s execution was duly stayed. But the response from the pro-death penalty lobby was fierce. First the Governor tried to illegally override the courts and reinstate the executions. (Governor Mary Fallin had memorably once exhorted her state to pray for rain – it failed). Then a Republican Congressman named Mike Christian threatened to impeach the five judges who voted for the stay. Fearful of losing their jobs, the justices caved.

Few states feel as strongly about the death penalty as Oklahoma. Though it executes fewer people than Texas, it has the highest executions-per-capita rate in the country. And it has played a pivotal role in the death penalty’s history – the state that gave the world the lethal injection, has also, with Lockett, inadvertently made about the best case for its repeal. Today, all eyes are on Oklahoma – rightly or wrongly, it has become an example to the world of how the death penalty is conducted in America.

So far, the official response has been underwhelming. Despite all the damning inquiries and investigations post-Lockett, the best the Department of Corrections could come up with was doubling down on lethal injection. In October, they took reporters on a tour of their all new execution chamber with its top of the line gurney and their machines that go ping - an EKG to monitor heart rate, and an ultrasound machine to help locate veins. The bed is referred to as a “multi-layered restraint system.”

At best, its lipstick on a pig. At worst, it compounds the original perversity of disguising killing as healing. None of the core problems have been addressed - the drugs embargo remains, the secrecy surrounding the compounding pharmacies still stands. And in a move that speaks volumes, the number of media witnesses has been reduced from 12 to 5.

It surprised no one when the firsts execution, scheduled for November 13th, was postponed. The official reason? They don’t have the right drugs and their staff aren’t yet adequately trained. Plus ca change. They’ve since been rescheduled – Charles Warner will be put to death on January 15th.

But there has been one development, courtesy of Mike Christian, the Republican Congressman who threatened to impeach his state’s Supreme Court judges. It’s not official yet, just an idea he’s working on – an all-new splatter free method that might just rehabilitate the death penalty once again, and continue Oklahoma’s proud tradition of innovation when it comes to strapping bad guys down and killing them.

He was watching a BBC Horizon documentary from 2008 called The Science of Killing, in which former MP, Michael Portillo, said that nitrogen could cause a painless death in about 15 seconds. So Christian took it to the legislature and proposed a method whereby the condemned is given inert gas to inhale, while they exhale naturally. At a presentation before the judiciary committee this September, he compared the sensation to ‘hypoxia’, the effect of oxygen deprivation on pilots and divers. His colleague, an assistant professor of Criminal Justice at a local university, compared the experience to euphoria. He played the committee YouTube videos of people breathing helium balloons, giggling and passing out.

Already pro-death penalty groups are rubbing their hands with excitement. Michael Rushford of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, for instance, is convinced that nitrogen is the future.

“It removes every problem that death penalty opponents have created,” he says. “And if Oklahoma manages successful executions this way, then other states will quickly go there and they’ll never be able to attack the method again. Think about it – it’s freely available, you can just go to the hardware store and buy tanks of it. You don’t need a doctor – anyone can administer it. It’s perfect. All you need is a mask and a tank of gas. Just turn on that Ethel Mermen music and off you go!”

It brings to mind that Mark Twain line, about how history doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes. Just like the lethal injection, here’s a method from Oklahoma that promises a brave new world of painless death, both swift and humane, without splatter or stench. There’s no suffering. The condemned just drifts blissfully into death. What could possibly go wrong?