On Not Having Kids

Esquire’s Sanjiv Bhattacharya has reached his mid-forties without having kids. Now it looks like he won’t ever be a father. And he’s fine with that. Isn’t he?

By Sanjiv Bhattacharya

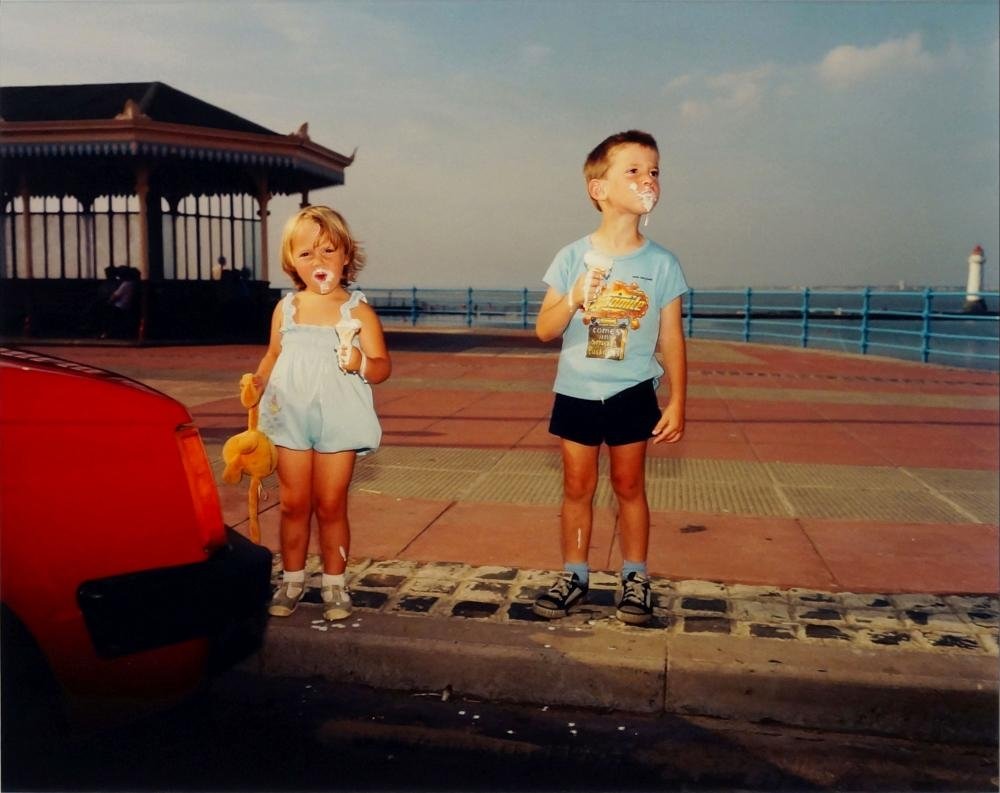

Photography: Martin Parr

First published by Esquire (UK), May 2016

I LIKE A HOUSE PARTY AS MUCH AS THE NEXT GUY. But this one? Not so much. The dress code appears to be bibs and blankets. People are drinking warm milk, which they can barely keep down. And it’s hard to get a conversation going. I tried chatting to the host just now – let’s call him Leo – but he barely said a word. Mostly he just held my finger.

Leo turned one today. Hence the party – a swarm of moms and babies giving it the full coochie-coo. It’s not my usual Saturday afternoon, but his parents are friends and we haven’t seen them in ages. We used to play tennis together, and drink Scotch in this very apartment. But then Leo moved in, cancelled tennis and now, our single malt tasting room is literally crawling with his closest friends. They’ve filled the place with strollers, bottles and Fisher Price whatevers. And the music these kids are into, it’s just the same song on repeat. I get it – the wheels on the bus are going round. They’re wheels.

Being childless, it’s hard not to feel like an interloper at these things. You don’t show up at a BYOB event without bringing your own baby, and yet here we are, my wife and I, looking a bit lost and wondering if it’s too soon to make an exit. We serve no purpose here, that’s the trouble. This is the realm of women with papooses and leaking breasts; grandmothers playing peekaboo; and dads who hover like Secret Service, ready to catch or grab at a moment’s notice. Us childless friends from a former life get spun out, as though by centrifuge, to the fringes of the party, the farthest orbits of irrelevance. We bring nothing to the discussion of nannies and pre-school and no one’s interested in the TV shows we’ve just binge-watched with all our glorious spare time. So we stand on the sidelines, observing the parents across a gulf, perplexed that such a distance should have opened up so quickly. When I watch friends disappear into parenthood, I often feel marooned, as though they’ve pulled away in a boat and left me on shore. But parties like this remind me that in fact, I’m the one on the boat.

“Want to hold him?” This always happens - a well-meaning parent tries to throw us a line before it’s too late. In this case, it’s Leo’s uncle, someone I’ve met a few times, but don’t know that well. He hands me his baby boy, we’ll call Jackson, who starts pawing at my face. It’s a matter of time, now. “Why don’t you and Mrs B make a baby?” he says. “Best thing I ever did.”

And there it is. The casual approach. Rather than tiptoe up to the question as if it might go off at any minute, just toss it out there like it’s nothing. Did you see the game last night? Ever thought of having a child? I could pause at this point, look at my shoes, and concoct some awful story about “the third miscarriage”. But why make it a production? Much better to just whip out my phone, show him pictures of the dogs and say, “We’ve already got our hands full with these two.” Keep it breezy. He’ll say “aww cute, is that a Boston terrier?” and I’ll say, “her name’s Onion”, and he’ll say “why Onion?” and the whole topic is safely averted.

But this guy won’t let go. He’s on this question like Onion on a chew toy. “No I mean human babies,” he says. “Like Jackson.”

“I’m just trying to keep my pre-baby figure,” I tell him.

“Seriously though, you must have a reason? Is it medical? I mean, you could always adopt...”

It’s not that he means to be rude. He just doesn’t realize – and neither did the cab driver, the insurance broker, the Fedex guy, or any of the others – that this question has tendrils in every corner of a man’s life. He’s putting me on the analyst’s couch next to a box of Kleenex. This is the thread that if you yank it, the whole coat unravels and leaves me standing there naked for all to see. Which is not a good look. Especially at a baby’s birthday party.

———-

Nonparents are pariahs. The stereotypes aren’t kind. Women are careerist and cold and traitors to their nature. Men are feckless and immature and traitors to their nature. Last year Meghan Daum edited a collection of essays on the topic, titled “Selfish, Shallow and Self-Absorbed”, which more or less covers it. Though one might add “Greedy” and “Incapable of Nurture.” Also, “Mildly Sociopathic”, because how else would you describe someone who hates children?

(For the record, I don’t hate children. Kittens and bunny rabbits can go fuck themselves, but children I’ve always liked. Except the ones on planes.)

I never thought I’d be this guy, the weird guy at the party without kids. But then, I never thought I’d be the other guy either. I just didn’t think, which explains a lot. I suspect that for many men, fatherhood is a distant train on the horizon that eventually pulls into the platform, either by accident or design. But it never loomed for me. Growing up I didn’t see myself as a father, or as anything else for that matter - I had no vision of the kind of adult I might become. All I knew was that I didn’t want to be like the adults I saw every day – my parents. Not because they’re bad people, they’re not, but because they were unhappy. We all were.

They’d had an arranged marriage. It was an extraordinary gamble. Within the space of 14 days, my father met my mother, married her, and then, to compound the upheaval, they moved from West Bengal to south London in the 1970s, where strikes were crippling the country and the National Front was on the rise. They’d each lived through hardship before, especially my mother – she’d have to break pencils in half to share with her siblings for school, the kind of shoeless poverty of the third world. But there were no friends or family around this time, they were in it alone – a couple of immigrants with ripe accents in a strange country that didn’t always want them. And to cap it all, they didn’t get along.

In the hierarchy of reasons why I’ve decided to remain childless my childhood is always up there. I wasn’t abused or neglected; I was privileged. My parents sublimated their strife into sacrifice and gave me a blue ribbon education, complete with clarinet lessons. But it was a joyless experience. That may sound like the smallest of first world violins after everything my parents went through, but these are the memories I have, the wounded impressions of a boy, mythologized over time. In our home children weren’t a delight but a battleground. And childhood wasn’t this pasture of innocence and discovery, but rather a grim staging ground for an even grimmer future to come. If there were a triptych, it would open with my father scowling in front of the television, followed by my mother seething in the kitchen, and then me in my room, dreaming of escape, each of us profoundly alone. It occurred to me, with a child’s logic, that if I had not been born, my parents might have divorced and led happier lives apart, so this was my fault, in a way. I spent eighteen years marinating in their resentment of each other, and then mine of them, a sauce that only thickened with time.

I’ve always seen my childhood and my childlessness as umbilically connected. But that’s not typical. For many, an unhappy childhood is as much a motive to have kids as a deterrent. Rather than avoid family life, I might easily have resolved to create the happy family I never had. Conversely, plenty of childless people come from perfectly happy homes. Everyone reaches this decision by their own path. No two snowflakes are alike.

I learned this from hanging out on the Childless by Choice Project Facebook page. It’s a small group, with a 1000 or so members, most of them women (about 4 out of 5) which is typical of the nonparent subculture. And they’re a feisty lot, defiant and defensive, as though a stand is being taken, and parents and nonparents are somehow at odds, each sniping at the other - you’re selfish! No, you’re selfish!

Popular posts often show children or parents in a negative light - a story about a delinquent mother, say, or a video of a toddler throwing a tantrum in a restaurant (sample caption: “your child should be in commercials…. For Trojan.”) Parents are called “breeders”, a term of contempt. And nonparents are described as “child-free” which they prefer to “childless”, since it denotes liberty rather than lack, while placing children in the same syntactic class as gluten, smoke and STD’s. There are frequent complaints about being asked “the question”. And several posts simply gloat about the child-free lifestyle - the full night’s sleep, the impulsive travel, and a home that hasn’t been entirely colonized by Dora the Explorer.

“It’s human nature to rationalize,” says Laura Scott, the page’s founder. A life coach from Florida, she wrote a book in 2004 titled “Two Is Enough”. “Parents go to the nth degree to rationalize their decision to have children, even though it can be very challenging. And childfree people do the same.”

It’s true. Ever since I moved to the Eastside of Los Angeles, I haven’t stopped slagging off the Westside (the side with all the douchebags). We naturally re-sell ourselves on our past decisions, and the bigger the decision, the harder the sell. But it has given this community - and so much of what’s written about childlessness - a tone of retort and counterargument. And the empathic gap between parents and nonparents only seems to widen.

Scott says her members are just reacting to the stigma of childlessness, which is a serious issue, especially for women. But the antipathy towards children is real. Scott, for instance, is a perfectly pleasant woman who genuinely doesn’t want to hold your baby. “Anyone under the age of 12,” she says. “I just don’t have an affinity.” And more dyspeptic voices are easily found. “I call them small mammals,” says Paul, a scientist from Oxford, in his fifties. “They don’t give me or my wife any warm feelings. Parents make these nebulous statements about the deep positive stuff that children bring into your life, but that’s all bullshit - justification after the fact. Mind you, I’m highly educated, so I’m able to reflect on these things. I don’t like to talk to anyone until they’ve got a college degree!”

I struggle with this, having been a child once myself. I still am in many ways. I thought we all were. Ted Hughes described our inner child as “that little creature sitting there, behind the armor, peering through the slits”. I’ve always found those little creatures quite charming. They’re silly and curious, they like a giggle - these are fine qualities at any age. In fact, I’ll go out on a limb here, and I don’t care if I take heat for this: I believe children are the future. We should teach them well and let them lead the way.

And yet, the likes of Paul and Laura are not as aberrant as they might sound. Birth rates are dropping throughout the developed world. The “little creature” is falling out of favor. And for the first time ever, there’s actually a sound moral argument to be made for not procreating: The planet needs a breather and going childless is as green as it gets. I could leave a stretched Hummer idling in my drive all day, while I burn tyres in my backyard, and I’d still do less damage than your average dad.

But the eco-argument is seldom the real reason for going childless. At best, it’s a shield against the critics. My reasons, like everyone else’s, are personal. That’s not to say that broader trends haven’t been an influence - they have. Only it wasn’t environmentalism in my case, it was self-actualization.

The psychologist Abraham Maslow explained human motivation via a pyramid, his famous “hierarchy of needs”. At the bottom are basics like food and water. Then as you move up the pyramid, through safety, relationships and social standing, you reach the apex - self-actualization – the drive to fulfill our creative potential and be all that we can be. This is the narrative of our times. We may be the first generations for whom parenthood is an option and not an expectation. Rather than produce a 2nd generation for tribe, faith or country - groupings that are losing their hold - our first loyalty is to ourselves, to pursue happiness and maximize our lives. The opportunities are unprecedented. We live longer than ever, the world’s knowledge is at our fingertips. This is the age of the life hack, the bucket list, and “having it all”, that greedy phrase. So the question becomes - will a child enhance that ride, or derail it?

This may not be as indulgent as it sounds. If I haven’t found happiness myself, how can I pass it onto a child? As the in-flight safety demonstration says - “make sure your mask is properly fitted before helping someone else.” We know that the best parents are happy parents; that happiness like misery is a communicable condition. I learned this much as a child.

And there’s something irresistible about seeing life as full of potential. It’s the essence of youth. Nonparents bristle at the Peter Pan stereotype, but I want to be young, more so now than ever. The graph of happiness over a lifetime is a U-curve and the 40s are in the middle, the sag of the sofa – this is the part where you realize your life hasn’t gone according to plan, or that it has, and it still hasn’t fixed what ails you. That’s where I live - the American Beauty years, a river in Egypt. I listen to house music on the treadmill. I know all the words to “Hotline Bling”. I take comfort in the delusion that my clay hasn’t set yet, and that my possibilities in this life are many. Parents are beholden and encumbered. All children are anchor babies in a certain sense. But I’m free to wander as I please, or so I like to think.

Will Self once said that until you have children, you are essentially a fictional character. You can always write yourself a plot twist, change your name, change your life. But children put an end to all that – they require parents to be pillars of consistency, so that they can be the ones who change. The life of possibilities is now theirs. I’ve never quite shaken off the sense that a child might be the death of hope for me. There’s a teenage terror of closing doors that were once open, whether we went through them or not. Children bring with them a mortal reminder; all being well, they’ll put you in the ground, those kids. And permanence terrifies me. I don’t even have a tattoo.

I’m also not much of a pillar. Stability was never a strong suit. When I met my wife, over a decade ago, I’d just moved to Los Angeles from London, and bounced from one chaotic start-up to the next. Hardly a candidate for fatherhood. But my wife didn’t mind. She’s never felt the urge to squeeze a cantaloupe through a straw. And I too lack the drive to force my genes into the world. I don’t need that illusion of continuity. Sex is one thing, but babies? Why create a half-me, when I can barely face the full-me in the mirror each morning?

Besides, when we first discussed it, we had no room for a child, quite literally. We were practically living in a studio - not so much at the top of Maslow’s pyramid as dragging the boulders into place for the foundation. Why plan an heir, when all they’d inherit was air? We’d both made a late start in a dicey line of work - she writes scripts, I write articles. And we were free agents, living that wobbly life of feast, then famine, then more famine, then OK, that’s enough famine, I’m not kidding, it’s getting cold in here. Freelancing has its moments, especially in LA where the ability to say fuck it and drive to the beach is really quite something. But instability is hard. Life takes on a lurching rhythm. To bring a child into our home would be like chucking a baby onto a passing rollercoaster.

We’re a steadier ship today, no doubt. And adoption hasn’t been entirely ruled out - it’s got “option” in the name, after all. But we view it the way a wingsuit daredevil judges the weather before leaping off a mountain - conditions need to be perfect. Can we afford nannies and sitters and private school and soccer camp? And will we have time to play catch and watch endless reruns of Barney the Dinosaur, because it’s just not right to let the help raise your children... And every time, we end up in full agreement that one of us will have to be the stay-at-home parent. At which point, it goes quiet, and I usually receive an email that can’t wait. “Sorry, dear, can we do this later? Only Banana Republic is offering 40% off …”

Then comes the harder question: Could I give a child a happy life? Childlessness is often framed as selfishness, but there’s no arguing with the Philip Larkin poem: “they fuck you up your mum and dad, they may not mean to but they do.” It happened to me, to some extent, and it’s not a tradition I want to continue. As I get older, I find it easier to come to terms with the harm I’ve suffered, rather than the harm I’ve inflicted. Increasingly, the Hippocratic oath seems the wisest course - first do no harm. I think I’d make a decent uncle - uncles get to go home afterwards. But fatherhood is 24/7, good days and bad. And a child doesn’t need my bad days. A child needs a pillar with a sunny disposition. I know what effect unhappy parents can have, and I’ll admit I’m no Labrador pup most mornings either. I’ve done my time on a therapist’s couch. I’ve heard him say “that’s your mother talking.” So I worry that my baggage will go once more around the carousel, and that one day, my child might be on a similar couch talking about me.

“Oh don’t worry, we all fuck them up!” That’s what other dads tell me. They’re so cavalier, I like that about them. A spot of psychological damage is par for the course, and anyway, the age of therapy has made for better parenting. We know better now. One generation improves upon the next, like iPhones.

Only I’m not so sure. As I reach my middle years – the age my parents were when I was a child – I find I share many of their design flaws, more so than improvements. I have my father’s gestures, his way of sitting and clearing his throat; I have my mother’s weak ankles, her anxiety. Either by nature or nurture, I’m less free of them, than I once hoped. Would I really be a better parent, or do I flatter myself?

—————

There was a cover of Time in 2013 with the headline: “The Child-Free Life: Why Having It All Means Not Having Kids”, and it featured a smug couple on a beach living the high life (I think they came from the Westside of Los Angeles.) This is a common perception of the childless – as people who surveyed the options and chose self-gratification, a life without responsibilities. And it leaves me cold. I made no such choice. And I can’t imagine advocating for childlessness that way, I’m far too conflicted about it. In fact, I struggle to understand people who aren’t. Some men get vasectomies in their early 20s, they’re so certain, and decades later, they claim to have no regrets. But my life isn’t like that, all planned out and regret-free. It tumbles along, and I blunder through, making choices that can’t be unchosen, this is true, but childlessness wasn’t one of them. It was a consequence, a side effect, not a goal. Though I try to deny it, life is a winnowing of options in the end as we become the product of our decisions, whether we meant it or not. And in this way, the reasons for not having children have accumulated through the years, like snow against a barn door. Leave it long enough and it just won’t open anymore.

Lately – to show you how conflicted I am - I’ve been thinking that parenting might actually be the best path to self-actualization. Surely, it builds our better natures to be depended on, to experience that epic bond? Parents learn to be responsible, playful, forgiving of spillage - less caught up with surfaces in general, given that most surfaces will be covered in ketchup eventually. Besides, I like doing kid stuff. The childless life can feel a bit desiccated at times. Lego and potato painting beats sipping Chardonnay and talking about real estate. Why lie on a beach like that Time Magazine couple when you can build sandcastles and play Frisbee? (Not that grown adults should play Frisbee with each other. There are some things you need a child to get away with.)

We were driving home the other day - my wife, the dogs and I - when the traffic narrowed to one lane, slowing to a crawl. And from every direction, children flooded into the street, all dressed in Halloween costumes. For five long minutes they streamed between the cars with their parents, all these adorable little Batmen and Tinkerbells. It was some sort of community get-together with jelly and ice cream, and kids running around with light sabers. And it was such a life affirming scene, I felt the sadness in my chest. The path not taken has seldom looked so picturesque.

These poignant moments, they happen all the time. Families are inescapable – in malls, on billboards, on television. From my desk at home, I hear a primary school at the bottom of the hill, the sound of recess, yelping and chasing and playing. And it puts me on that boat again, drifting away from shore, feeling left behind. When I expressed this to Paul, the Oxford scientist, he scoffed. “I find it sad,” he says. “Why do people have to join the herd? Why can’t they create their own individual identity as I’ve always done?” Granted, Paul might not best person to talk to if you’re feeling vulnerable. But it’s a fair point. I scorned the herd as a younger man, but now I wonder. Matters of identity and purpose aren’t so straightforward for a childless freelancer in Los Angeles, the international capital of the untethered. It’s always a nice day for an existential crisis out here, and us childless have all that extra time in which to ponder. So as we left the Halloween pastoral, the usual questions churned. Who am I doing this for? Why do I exist? What use is all my self-actualization – my insight and experience - if I can’t dump it all onto a small child?

We went home that night and hugged our dogs extra tight. We didn’t dress them up as zombies, but maybe next year. Maybe that’s what happens to people like us. The childless often call other things “babies” and there’s no question, those dogs, Onion and Cujo, are our furry surrogates – our furrogates. We all, even Paul, need small creatures to cuddle, a bit of coochie-coo in our lives. And dogs won’t end up on a therapist’s couch (they knows they’re not meant to be on the couch anyway.) Some of them can even play Frisbee.

It’s also true that they won’t visit us as we crumble away in a rest home. They won’t say “Dada” or graduate or give us grandchildren. But it’s best not to dwell on such things. This is our life and we must embrace it. Be grateful, do not hanker – that’s what the wise ones say. While I’ll miss out on the joys of Halloween, I can at least try to self-actualize and create “book babies”, an idea I’ve always liked. After all, childlessness offers what books require – acres of time and silence. Only it’s never quite silent, not for me. There’s always the sound of recess.